The Cool Rockin’ Daddies will play at Arts in a Roadhouse from 3 to 7 p.m. Sunday at River Grove Moose Lodge, 8601 W. Fullerton Ave., River Grove. Tickets are $20; kids ages 6-16 are $10. Proceeds benefit the Caring Arts Foundation, a nonprofit that brings art to hospitalized cancer patients. For more information, visit caringarts.com. — Promotional image

The Cool Rockin’ Daddies will play at Arts in a Roadhouse from 3 to 7 p.m. Sunday at River Grove Moose Lodge, 8601 W. Fullerton Ave., River Grove. Tickets are $20; kids ages 6-16 are $10. Proceeds benefit the Caring Arts Foundation, a nonprofit that brings art to hospitalized cancer patients. For more information, visit caringarts.com. — Promotional image

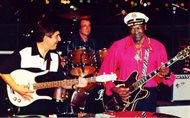

Joe Gagliardo plays with the legendary Chuck Berry at Hawthorne Race Course. — Submitted photo

Joe Gagliardo plays with the legendary Chuck Berry at Hawthorne Race Course. — Submitted photo

Joseph M. Gagliardo strums the bass at Buffalo Grove Days on Aug. 29 with his band, the Cool Rockin’ Daddies. A longtime musician who once played on stage with Chuck Berry, Gagliardo is the managing partner of Laner, Muchin Ltd. — Michael R. Schmidt

Joseph M. Gagliardo strums the bass at Buffalo Grove Days on Aug. 29 with his band, the Cool Rockin’ Daddies. A longtime musician who once played on stage with Chuck Berry, Gagliardo is the managing partner of Laner, Muchin Ltd. — Michael R. Schmidt

The Cool Rockin’ Daddies, with bass player and lawyer Joseph M. Gagliardo (center), on stage at Buffalo Grove Days on Aug. 29. — Michael R. Schmidt

The Cool Rockin’ Daddies, with bass player and lawyer Joseph M. Gagliardo (center), on stage at Buffalo Grove Days on Aug. 29. — Michael R. Schmidt

Joseph M. Gagliardo got the call a week before the show.

“Are you interested in playing with Chuck Berry?” a promoter asked Gagliardo, who plays bass guitar.

Gagliardo figured he was looking for an opener.

“No,” the promoter said. “He doesn’t travel with a band, so if you get a drummer and a piano player, the show’s yours.”

Gagliardo hung up and started making calls. He knew Berry’s reputation as an ornery perfectionist. The musicians who turned Gagliardo down did too.

“The first couple people I called were concerned that it could turn out to be an unpleasant situation,” Gagliardo said. “I thought it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and I was going to take the chance.”

For Gagliardo — managing partner at Laner, Muchin Ltd. — that gig in the early 2000s remains a career highlight. He was paid $50 for his performance, a fee he would have gladly waived.

On Sunday, he and his band Cool Rockin’ Daddies will play pro bono for a different reason — to help raise money for cancer treatments at a Caring Arts charity concert.

“I view music as … something that’s positive in people’s lives,” he said. “This applies whether we’re playing a small show or a large show — we always put out 1,000 percent.”

When Gagliardo played with Berry, 1,000 percent was necessary.

“Chuck Berry’s stuff is mostly a three-chord progression, so it’s not difficult,” said Dan Buck, the lead singer of Cool Rockin’ Daddies. “The difficult part is following Chuck.”

That’s because Berry plays without a set list.

“You essentially have to immerse yourself in Chuck Berry music, because you don’t know what he’s going to play,” Gagliardo said. “He doesn’t even tell you what keys the songs will be in.”

Gagliardo spent a week before the show listening to and practicing Berry’s songs. He estimates he prepared “somewhere in the neighborhood of 75 to 80 songs.”

In the hourlong show, the band played “maybe 15.”

If anyone was equipped to absorb a rock ’n’ roll legend’s catalog in a week, it was Gagliardo.

“He’s like an encyclopedia,” Buck said. “I thought I had a good handle on rock music history, but this guy’s unbelievable. When I get stumped, I give Joe a call. He’s that good.”

Part of Gagliardo’s talent remembering songs stems from his music collection. He owns about 5,000 vinyl albums, 5,000 45 rpm records and “I don’t know how many CDs.”

But part of it is his memory, which he utilizes as much in court as he does on stage.

“The importance of my memory as an attorney is the ability to remember facts that did not appear to be important at an earlier point of time that now can be critical to the development and presentation of a case,” said Gagliardo, a labor and employment litigator.

After graduating from The John Marshall Law School in 1977 and running his own shop for a year, Gagliardo became a Chicago assistant corporation counsel in 1978.

He was there for a decade, moving his way up to first deputy corporation counsel while working with mayors Michael Bilandic, Jane Byrne, Harold Washington and Eugene Sawyer.

In 1988, Gagliardo joined Laner, Muchin as a partner heading up the firm’s litigation group and continuing his labor and employment work, representing employers. His clients have included Oprah Winfrey’s Harpo Studios, Donald Trump and the state of Illinois during the administrations of Jim Edgar, George Ryan, Rod Blagojevich and Patrick J. Quinn.

“He is one of the most practically minded lawyers I have ever known,” said Jeffrey S. Fowler, a partner at Laner, Muchin who met Gagliardo in 1994.

“He seemed to have a good focus about how to get from point A to point B … focusing on the best route to get to the best legal result.”

His work representing state government included AFSCME v. Weems, a 2012 case in which the state’s largest public employees union alleged that Quinn’s plans to close two youth detention centers and eight Department of Corrections facilities were being made without adequate preparation for the safety of prison employees.

The Illinois Supreme Court eventually ruled in the state’s favor and the facilities were closed.

Gagliardo also defended the city of Chicago during Michael L. Shakman’s ongoing litigation over political hires.

“One of the benefits of working for the government, whether you’re an in-house lawyer or an outside lawyer, is that you have a chance to be involved in cases that promote change on a wide-scale basis,” Gagliardo said.

His interest in government work started in high school, when he read Anthony Lewis’ book “Gideon’s Trumpet” about Gideon v. Wainwright, the landmark Supreme Court case that gave criminal defendants the right to free legal counsel.

“The book piqued my interest in the law because it showed me that a lawyer could have involvement in a case that influences the law across the nation,” he said.

Video: Gagliardo performs with the Cool Rockin' Daddies

Gideon was decided in 1963, the year Gagliardo turned 11. The next year, the Beatles played on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

“When the Beatles and the British Invasion hit, it inspired many kids to play an instrument,” Gagliardo said. “I was one of those kids.”

He was already a pop music fan. At age 5, he got his first 45 record — “At the Hop” by Danny and the Juniors. His first Chuck Berry 45 was “Sweet Little Sixteen.”

“I didn’t have a bunch of 45s, so whatever I had, I used to play a lot,” he said.

Gagliardo picked up the guitar in grammar school and switched to the bass soon after. He and some friends started a band called The Belvederes, named after the Plymouth car, and he continued playing in bands throughout high school and college.

He stopped when he went to law school, then resumed 21 years later.

He has played for the past 11 years with Buck and three others in Cool Rockin’ Daddies, a self-described “roadhouse-style” band that has opened for Cheap Trick, Heart, Ted Nugent and ZZ Top.

The band’s next gig on Sunday supports Caring Arts, a nonprofit that brings art to hospitalized cancer patients. Gagliardo serves on its board of directors.

“It’s a very different Joe — the rocker Joe versus the managing-partner-of-a-law-firm Joe,” Fowler said. “And then seeing him on stage with a T-shirt rocking out with a bass guitar is such a contrast. I get a big kick out of it.”

To this day, Gagliardo still enjoys recalling his time on stage with Berry, a capacity show at the Hawthorne Race Course that drew about 2,500 fans. Berry’s instructions to the band were as simple as they were perplexing.

“I’m going to go out there and start playing Chuck Berry songs,” Chuck Berry said, “and you guys jump in.”

There was only one stipulation.

“I want you to play very simply,” Berry said.

After three or four songs, Berry changed his tune.

“You’ve got it,” he told Gagliardo and the band. “Play what you want.”

“It was an honor,” Gagliardo said. “I was probably beaming.”

Then it happened. Berry started playing “Sweet Little Sixteen.”

“My heart started pumping,” Gagliardo said. “I could picture watching that 45 spin on the turntable and listening to it over and over again as a kid.”

Berry may be a prickly performer, but he spent that night vibing and smiling on stage with Gagliardo and the band.

At the end of the show, he bowed to all three men and walked off the stage while they finished the set.

Afterward, the sound man approached them.

“Man,” he said, “he really liked you guys.”